Eric W. Dolan March 6, 2022 Cognitive Science

The type of education a child receives appears to influence how they represent knowledge in long-term memory, according to a new study published in the journal Science of Learning. The findings indicate that Montessori students tend to have a more richly connected network of semantic memories.

“We are facing many changes, and education seems to be a crucial point to prepare young people to face these changes. However, we do not yet have an educational system based on a thorough knowledge of child development. There is an urgent need to deepen our understanding of child development, using comparative studies, to improve and provide the best possible educational practices and environments for children,” said study author Solange Dénervaud, a postdoctoral fellow at the Lausanne University Hospital.

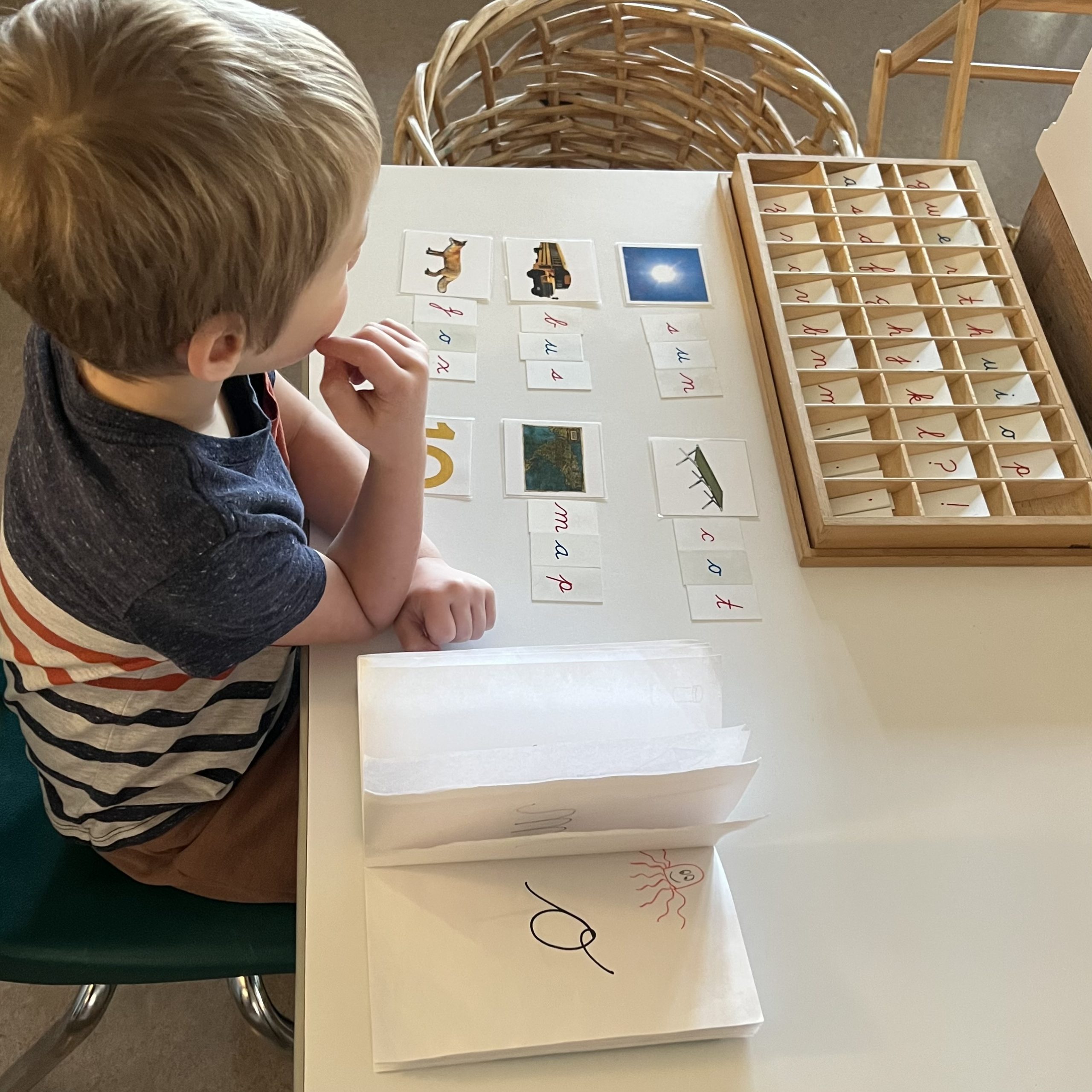

The researchers were particularly interested in determining the long-term effects of Montessori versus traditional education. Children in Montessori classrooms can freely choose from a range of learning activities in multi-age classes. Traditional education, in contrast, focuses on teacher-directed learning activities.

In the study, 67 Swiss children completed a verbal fluency task in which they were asked to name as many animals as they could. The researchers then conducted a semantic network analysis on each child’s responses to assess how the animals were organized in memory. “Semantic network analyses depict each concept (name) as a node, and relations between them as edges. Thus, the less related the concepts, the longer the edges (e.g., pear and avocado vs. pear and apple), but also the slower the participant will be to report their relationship,” Dénervaud and her colleagues explained.

The children also completed measures of convergent and divergent creativity. Convergent creativity represents the ability to generate a single optimal solution to a problem, while divergent creativity represents the ability to generate many solutions to a problem with several possible answers.

The researchers found that children who had been educated in Montessori schools tended to have a more “flexible” semantic network structure. In other words, Montessori-educated children tended to exhibit more connections and shorter paths between animal concepts compared to children who received traditional education. Montessori-educated children also had higher scores on the tests of creative thinking.

“What we learned from this study, and what is important to understand, is that the quality of learning is more fundamental than the quantity. The more concepts are memorized with meaning, with experience, with involvement, with pleasure and personal understanding, the more they will be organized in memory in a flexible, diversified and enriched way,” Dénervaud told PsyPost.

“This has an influence on the child’s creative thinking, who will therefore use his or her knowledge in the same way (versus in a rigid way). This is especially true during the developmental stage (between about 6 and 12 years of age), when the child assimilates an immense number of new concepts each year.”

The two samples of children were matched on socioeconomic factors and nonverbal intelligence. But Dénervaud noted that researchers still have much to learn about how education styles influence cognitive outcomes.

“This is a study comparing two groups of children aged 6-12 years. It is essential that other studies replicate our results, and more importantly, follow the children through development to validate what we have observed,” she explained. “It is also important to study in more detail what aspects of pedagogy allow students to appropriate concepts in a flexible and enriched way: peer learning? The absence of a grade? Active learning? We do not have an answer to this question at this time.”

“This study does not aim to promote a pedagogical approach, but really to better approach the reality of the child,” Dénervaud added. “Who are they and how do they learn? By comparing relatively opposite approaches, it reveals interesting differences for a scientific understanding of child development.”

The study, “Education shapes the structure of semantic memory and impacts creative thinking“, was authored by Solange Denervaud, Alexander P. Christensen, Yoed. N. Kenett, and Roger E. Beaty.