Excerpt from Autism and Education: The Way I See It, What Parents and Teachers Need to Know by Dr. Temple Grandin

I had a wonderful and effective early education program that started at age two and a half. By then, I had all the classic symptoms of autism, including no speech, no eye contact, tantrums, and constant repetitive behavior. This was in 1949, and doctors knew nothing about autism, but my mother would no accept that nothing could be done to help me. She was determined and knew that letting me continue without treatment would be the worst thing she could do. She obtained advice from a wise neurologist who referred her to a speech therapist to work with me. She was just as good as the autism specialist today.

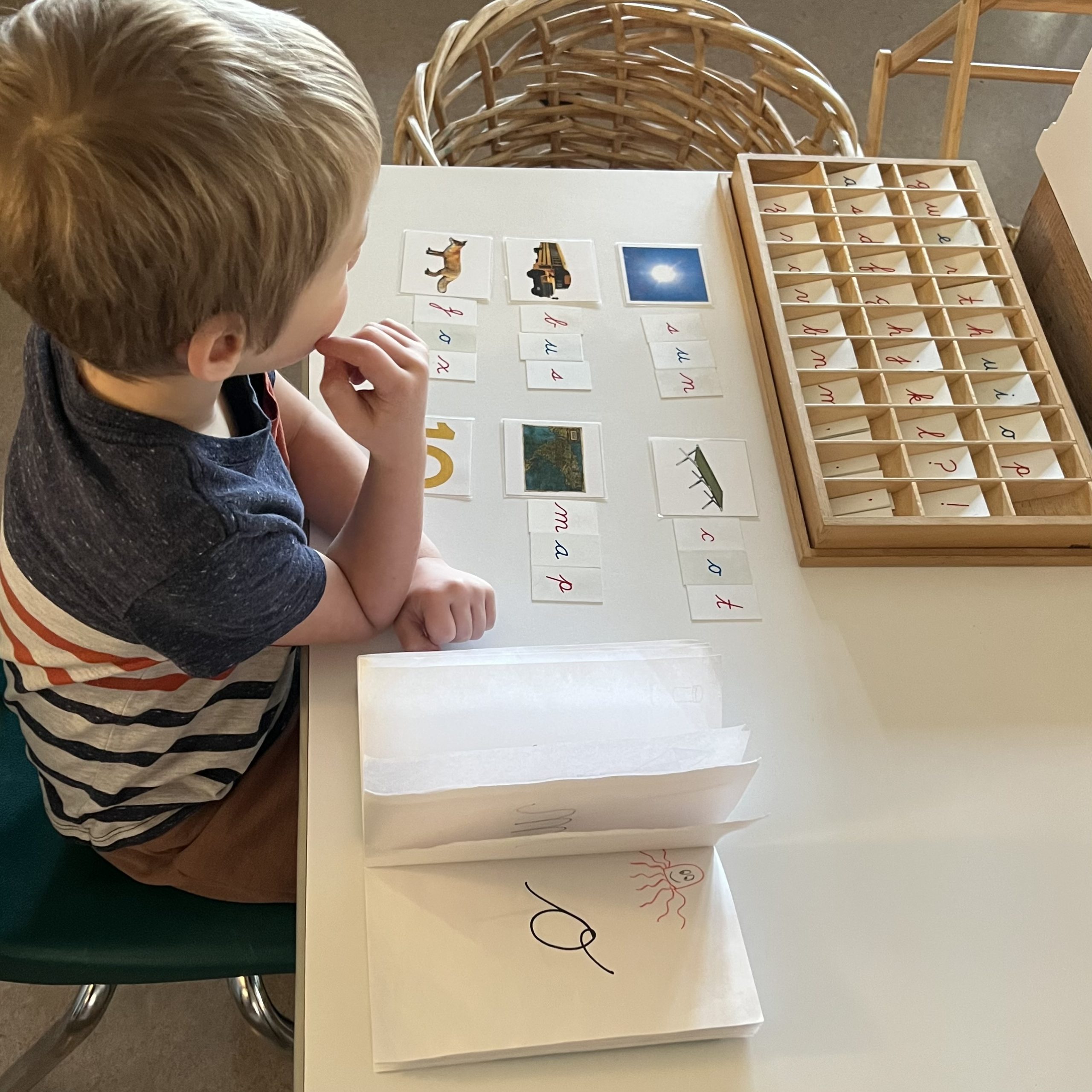

My talented speech therapist worked with me for three hours a week dong ABA-type training (breaking skills down into small components, teaching each component separately using repetitive drills that gave me lots of practice) and she carefully enunciated hard consonant sounds so I could hear them. At the speech therapy school, I also attended a highly structured nursery school class with five or six other children who were not autistic. Several of the children had Down syndrome. These classes lasted about eight hours a week.

My nanny was another critical part of my early therapy. She spent 20 hours a week keeping me engaged. For instance, playing repeated turn-taking with my sister and me. She was instrumental in introducing early social skills lessons, even though at that time, they weren’t referred to as such in a formal manner. Within the realm of play, she kept me engaged and set up activities so that most involved turn-taking and lessons about being with others. In the winter, we went outdoors to play in the snow. She brought one sled and my sister and I had to take turns sledding down the hill. In the summer, we took turns on the swing. We were also taught to sit at a table and have good table manners. Teaching and learning opportunities were woven into everyday life.

When I turned five, we played lots of board games such as Parcheesi and Chinese checkers. My interest in art and making things was actively encouraged and I did many art projects. For most of the day, I was forced to keep my brain turned into the world. However, my mother realized that my behaviors served a pupose and that changing those behaviors didn’t happen overnight. I was given one hour after lunch where I could revert back to repetitive autistic behaviors without consequence. During this hour, I had to stay in my room. I sometimes spent the entire time spinning a decorative brass plate that covered a bolt that held my bed frame together. I would spin it at different speeds and was fascinated at how different speeds affected the number of times the brass plate spun.

The best thing a parent of a newly diagnosed child can do is to watch their child without preconceived notions and judgments and learn how the child functions, acts, and reacts to his or her world. My book, Navigating Autism, will help prevent parents from becoming label-locked and underestimating the abilities of their child. That information is invaluable in finding an intervention method that will be a good match to the child’s learning style and needs. The worst thing parents can do with a child between the ages of two to five is nothing. It doesn’t matter if the child is formally diagnose3d with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or has been labeled something less defined, such as global developmental delay. It doesn’t matter if the child is not yet diagnosed if there are signs that the child may be on the spectrum: speech is severely delayed, the child’s behaviors are odd and repetitive, the child doesn’t engage with people or his/her environment, etc. The child must not be allowed to sit around stimming all day or, conversely, tuning out the world around him/her. Parents, hear this: doing nothing is the worst thing you can do. If you have a three-year-old with no speech who is showing signs of autistic behavior, you need to start working with your child now. If signs are appearing in a child younger than three, even better. Do not wait six months or a year even if your pediatrician is suggesting you take the “wait and see” approach or is plying you with advice such as “boys develop later than girls” or “not all children start to speak at the same time.” My advice is to act now is doubly emphasized if your child’s language started developing late or his/her language and/or behavior is regressing.

Parents can find themselves on long waiting lists for both diagnosis and early intervention services. In some cases, the child will age out of the states’s early intervention system (birth to three) before his name gets to the top of the list! There is much parents can do to begin working with the child before formal professional intervention begins. Play turn-taking games and encourage eye contact. Grandparents who have lots of experience with children can be very effective. If you are unable to obtain professional services for your youn child, you need to start working with your child immediately.

This book and Raun Kaufman’s book, Autism Breakthrough, will be useful guides on how to work with young kids. The best part of Kaufman’s book are the teaching guidelines that grandparents and other untrained people can easily use. Ignore his opinions about other treatments. Do not allow young children under five to zone out with tablets, phones, or other electronic devices. In young children, solitary screen time must be limited to one hour a day. For children under five, all other activities with electronic devices should be interactive activities done with a parent or teacher.

The intense interest in the electronic device can be used to motivate interest in doing a game where turns are taken with another person. During this game, the phone should be physically passed back and forth during turn taking. Too many kids are tuning out the world with electronics. In older children, video game playing should be limited to one hour a day. Excessive video gaming and screen use is a major problem in individuals with autism.

Engagement with the child at this point in time is just as effective as is instruction. While you may not be knowledgable about various autism intervention models, you are smart enough and motivated enough to engage your child for 20 plus hours a week. Don’t wait! Act now!

References and Additional Reading:

Adele, D. (2017) The impact of delay of early intensive behavioral intervention on educational outcomes for a cohort of medicaid-enrolled children with autism, Dissertation, University of Minnesota.

Ball, J. (2012) Early Intervention and Autism: Real Life Questions, Real Life Answers, Future Horizons, Inc., Arlington, TX.

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (2017) Evidence-based treatment options for Autism, www.chop.edu/news/evidence-based-treatment-options-autism (Accessed June 22, 2019).

Dawson, G. et al. (2010) Randomized controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Mode, Pediatrics 125:e17-e23.

Fuller E.A. et al. (2020) The effect of the early start Denver model for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Meta-analysis, Brain Science, 10(6)368.

Grandin, T. (1996) Emergence: Labeled Autistic, Warner, Books, New York, NY.

Grandin, T. and Moore, D. (2021) Navigating Autism: Nine Mindsets for Helping Kids on the Spectrum, Norton Books, New York, NY.

Gengoux, G.W. et al. (2019) A pivotal response treatment package for children with autism spectrum disorder, Pediatrics, Sept:144(3) doi:10.1542/peds.2019-0178

Kaufman, R.K. (2015) Autism Breakthrough, St. Martin’s Griffin.

Koegel, L. and Lazebnik, C. (2014) Overcoming Autism: Finding Strategies and Hope that Can Transport a Child’s Life, Penguin Group, New York, NY.

Le, J. and Ventola, P. (2017) Pivotal response treatment for autism spectrum disorder: Current Perspectives in Neuropsychiatric Disorders Treatment, 13:1613-1626.